On the recreational field of Newport Elementary, if the teachers were in charge, we would all pressed into playing team sports such as kickball, dodgeball, and four-square (all played with the same under-inflated maroon ball). If the teachers weren't in charge, if it was before or after school, or on cold days when they couldn't be bothered to come outside, there was only one game being played.

That game was called Smear The Queer. Sometimes we called it Kill The Creep, but it was the same game, a sort of a combination of tag and keep away. The Queer, or the the guy with the ball, would run away from everyone else and try to hold onto the ball until he was tackled and the ball was wrestled away from him by someone, who was then the new Queer. The ironic fact that the goal of the game was to BE the Queer, for as long as possible, was as lost on the other children as it was on me.

When I was much older, I learned that Smear The Queer was not unique to backwater North Carolina, probably any American kid that hit elementary school before the "politically-correct" era will remember the game. For me, it was those games of Smear The Queer that taught me, with finality, that I would never enjoy playing sports. I learned that not only was I unskilled and unpopular during the team sports that the school organized, but that even when I voluntarily entered into games that seemed fun to me, I was slow, uncoordinated, and gleefully targeted as easy prey by the rest of the children. I was never the Queer for more than a few seconds. Again, the irony is dizzying.

My father, the athletic Marine, the sports nut who played in any game offered by the enlisted leagues on the base, loathed my lack of interest in sports, possibly even more than my painfully apparent lack of abilities. The old adage that distant fathers create gay sons is backwards, by the way. The truth is that gay sons create distant fathers, at least in my case, a situation that I didn't suss out for many years.

He was embarrassed by me, this he made apparent at every dropped ball, at every missed lay-up. And yet, he forced me into playing Little League, pushing my inabilities onto the biggest public stage offered by a rural Southern town. And I resisted, as mightily as any 10 year old boy could. I tried to miss the try-outs by walking to the field, instead of riding with the kid next door as arranged. But by chance, my father passed me on the road and angrily whipped his car around to deliver me to the try-outs himself, cursing while I sobbed in the back seat.

The try-outs weren't really "try-outs" since every kid would be assigned to a team. The try-outs were actually just a method for the coaches to assess the talent pool and try to allocate each team an equal number of ringers and losers. Of course, the coaches were just busy-body Dads who were trying to advance their own sons at the cost of the other kids. If your Dad was a coach, you didn't end up on somebody else's team.

With my father looking on, I "tried out". At the plate, I missed all five of my pitches. I tried to make up for this by showing extreme enthusiasm when it was my turn to run the bases, but in my attempt to run as fast as any other kid, I tripped on second base and slammed face-down into the dry red clay. The other kids screamed in delight while I picked myself up and limped to home plate. Rounding third, I saw my father standing behind the fence, stone-faced.

My fielding test was just as bad. At second base, I missed every grounder. Trying to throw to home plate, I hit one of the coaches in the leg. That's when they moved me to right field. For those that don't know, right field is most ignominious position in baseball. Since 95% of batters are right-handed, almost all hits end up in left or center field. Right field is where you stick a kid if you just can't take a chance that the ball might come to him. And every kid knows that.

So I stood there in right field, with a handful of other equally sucky kids, while the coaches conferred over their clipboards and made the team allocations. I looked around for my father, but he had fled in shame. I bent over and pretended to pick at the grass to hide the tears.

Little League teams are named after their sponsors, which are usually local businesses or fraternal organizations. Like many small towns, we had teams named Rotary, Elks, and Moose. But we also had teams like The Varmints, sponsored by a pest-control company. There were The Belks, sponsored by a department store called Belk-Lindsey. Out of the 10 teams, I mostly feared being chosen for W.O.W., which was sponsored by a logging company's union, Woodmen Of The World. Naturally, the kids all called the team Women Of The World.

Surprisingly, when the teams were announced, I was very happy. I'd been drafted onto the same team as my best friend Gary Wilson, no doubt because his Dad, whom I really liked, was that team's coach. It was the only bright spot in a horrible day that started and finished with crying. I think I actually smiled on the walk home. I think I may have actually looked forward to playing, on the walk home. I think I may have playfully tossed my mitt into the air, on the walk home. (Although I probably didn't catch it.)

I walked into the house and proudly announced, "Mom! Guess what! I'm on DRUGS!"

My mother said, "Oh, that's nice honey. I was hoping you'd be on Drugs."

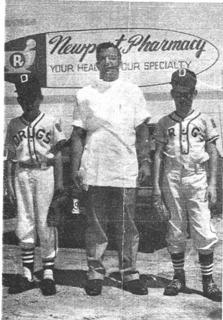

Yes, gentle readers, my first Little League team was called DRUGS. Proudly sponsored by local pharmacist and owner of the Newport Pharmacy, Seymour Rubin. We were not THE Drugs, just Drugs. The local paper once had the headline "Rotary Overcome By Drugs." That's me on the left, by the way. Just by looking at this picture, can't you tell the other kid is a much better player?

And can you imagine a Little League team called "Drugs" in 2005?

All the best players are on Drugs.

.